Written by Mariam Mokhtar

The Perak Mufti Harussani Zakarai’s freedom to ban just about everything in our lives is perhaps one of the reasons why the Malay youth of today is rebellious, uncontrollable and undisciplined.If the Malay/Muslim is not allowed an avenue to relax, to enjoy or be creative, and to have a bit of a laugh, he will grow up at worst, to be a miserable old grouch, possibly like Harussani or at best, he will end up non compos mentis.How on earth are Muslims going to live normally, if they are expected to be swathed in cotton wool throughout his life because the likes of Harussani think the Muslim is so weak and his soul so tormented, that he will be easily influenced by the devil or by the teachings of Jesus Christ?Harussani and the Perak Fatwa Committee, have decided that the poco-poco dance is haram for Muslims. According to him, the dance has elements of Christianity and soul worshipping.The Perak Menteri besar, Zambry Abdul Kadir, has agreed with the Mufti and said that all quarters should respect him and not create any dispute on the matter.

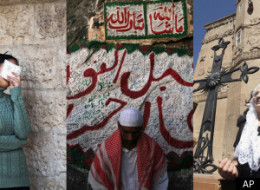

The three monotheist religious traditions, Judaism, Christianity and Islam, have more in common than in contention. All three believe God is one, unique, concerned with humanity’s condition. Each takes up the narrative of the others’ — Christianity and Islam carrying forward the story begun in the Hebrew scriptures of ancient Israel that define Judaism. Christianity affirms the vocation of Israel after the flesh, and Islam affirms the validity of the antecedent monotheist revelations, regarding Muhammad as the seal of prophecy and the Quran as a work of God. Falling into the genus of religion and forming a single sub-species of theistic religions, the three monotheisms among all theistic religions bear a unique relationship to one another. That is because they concur not only in general, but in particular ways. Specifically, they tell stories of the same type, and some of the stories that they tell turn out to go over much the same ground. Judaism, with its focus upon the Hebrew scriptures of ancient Israel, tells the story of the one God, who created man in his image, and of what happened then within the framework of Israel, the holy people. Christianity takes up that story but gives it a different reading and ending by instantiating the relations between God and his people in the life of a single human being. For its part, in sequence, Islam recapitulates some basic components of the same story, affirming the revelations of Judaism and then Christianity, but drawing the story onward to yet another climax. We cannot point to any three other religions that form so intimate a narrative relationship as do the successive revelations of monotheism. No other set of triplets tells a single, continuous story for themselves as do Islam in relationship to Christianity, and Christianity in relationship to Judaism. What demands close reading is this: Within the logic of monotheism, how do Islam, Christianity and Judaism represent diverse choices among a common set of possibilities?

The three religions of one God concur and contend. The basic categories are congruent, the articulation of those categories is not. By showing the range and potential of a common conviction — that God is one and unique, makes demands upon man’s social order and the conduct of every day life, distinguishes those who do his will from the rest of humanity and will stand in judgment upon all mankind at the end of days — the three religions address a common program. But differing in detail, each affords perspective upon the character of the others. Each sheds light on the choices the others have made from what defines a common agenda, a single menu: the category-formations that they share.

What are the theological issues subject to debate? • Does the interior logic of monotheism require God to be represented as incorporeal and wholly abstract, or can the one, unique God be represented by appeal to analogies supplied by man? In line with Genesis 1:26, which speaks of God’s making man “in our image, after our likeness,” and the commandment (Ex. 20:4), “You shall not make yourself a graven image or any likeness of anything” in nature, what conclusions are to be drawn? At one end of the continuum, Islam insists that God cannot be represented in any way, shape or form, not even by man as created in his image, after his likeness. At the other end, Christianity finds that God is both embodied and eternally accessible in the fully divine Son, Jesus Christ. In the middle Judaism represents God in some ways as consubstantial with man, in other ways as wholly other. • God makes himself known to particular persons, who, in the nature of things, form communities among themselves. God addresses a “you” that is not only singular, a Moses or a Jesus or a Muhammad, but plural — all who will believe, act and obey. Islam, Christianity and Judaism concur that the faithful form a distinct group, defined by those who accept God’s rule and regulation. But among all humanity, how does that group tell its story, and with what consequence for the definition of the type of group that is constituted? Judaism tells the story of the faithful as an extended family, all of them children of the same ancestors, Abraham and Sarah. It invokes the metaphor of a family, with the result that the faithful adopt for themselves the narrative of a supernatural genealogy, one that finds within the family all who identify themselves as part of it by making its story their genealogy too. Islam dispenses entirely with the analogy of a family, defining God’s people, instead, through the image of a community of the faithful worshipers of God, seeing Muslims as supporters of one another and caretakers of the least fortunate or weakest members of the community. Where Judaism speaks of a family among the families of humankind or of “Israel” as a nation unlike all others, sui generis, Islam takes the diametrically opposed view. Its “people of God” are ultimately extensible to encompass all humankind within the community of true worshipers of God. Here Christianity takes a middle position. Like Judaism, it views the faithful as a people, but like Islam, it obliterates all prior genealogical distinctions, whether of ethnicity, gender or politics. So Christians form “a people of the peoples,” “a people that is no people,” using the familiar metaphor of Israel. At the same time, they underscore, like Islam, a conception of themselves as comprised by mankind without lines of differentiation. • God has set forth what he wants from his people, which is the love and devotion of his creatures. This comes to realization in a program of actions to be carried out and to be avoided. These concern acts of prayer, study, contemplation and reflection on divine revelation (in the case of Judaism, study of Torah; in the case of Christianity, the realization and enactment of the image of Christ within the individual believer and the community; in the case of Islam, particular prescribed ritual acts of piety and worship: testimony of faith, ritual prayer, almsgiving, fasting, pilgrimage as well as recitation of God’s word, calling upon him in personal prayer and obedience to His will). All three also require deeds of philanthropy in charity and acts of loving kindness, above and beyond the requirements of the law. Judaism and Islam share certain food laws (e.g., not to eat carrion but to eat only meat from animals that have been properly slaughtered), and Christianity in its formative age forbade the faithful to eat meat that had been offered to idolatry. Where Islam requires a pilgrimage to Mecca, the observance of the festivals of Judaism encompassed a pilgrimage to the Temple in Jerusalem when it still stood and Christianity portrayed all the faithful as pilgrims to the new, heavenly Jerusalem that God was preparing for his people. In these and comparable ways, the three religions aim at defining acts that realize God’s will and that sanctify God’s people.

How is God’s people to relate to everybody else? What are the consequences of the conviction that the one and only God has made himself known to humanity at large through one community or person or family? Specifically, what is the task of the believer vis-à-vis the unbeliever? At one end of the continuum, Judaism asks the faithful to avoid participating in, or in any way affirming, the activities of the idolaters in their idolatry. Amiable relationships on ordinary occasions give way to strict isolation from idolatry and all things used in that connection. At the other end of the continuum, Islam, for reasons equally systemic, takes the most active role, undertaking to obliterate idolatry by wiping out its worshipers. Judaism in its classical statement defined its task as passive avoidance, joined with a willingness to accept the sincere convert. Islam called for active the extermination of idolatry, joined with an insistence that, to live, the idolater must renounce his error and acknowledge the one true God and his own. Yet, early Islam took a very different position vis-à-vis Jews and Christians and a few other “people of Scripture.” These were to be largely tolerated so long as they did not threaten Muslims or the practice of Islam. Christianity found its position in the middle. On one hand, like Judaism and Islam, Christianity forbade the faithful to utilize anything that could serve idolatry and to refrain, even at the cost of death (“martyrdom”), from all gestures of complicity with idolatry. On the other hand, like Judaism and unlike Islam, Christianity in its formative age contemplated not a holy war of extermination but an on-going campaign of evangelism, to win over idolaters. True, in due course, Christianity would slide over to the Islamic side of this continuum, but that happened many centuries beyond the classical age. In its formative centuries, Christianity’s logic dictated a policy toward unbelievers that placed the religion in the middle, between Judaic passivity and Islamic activity. • What of the end of days? Here is where the interior logic (as well as the articulation) of the three monotheisms both converges and diverges. As told in common, the story finds the resolution of the dialectic of how the one omnipotent and just God can account for a world of manifest injustice. All three religions concur that God will bring the end of days, when all mankind will be raised from the dead and judged, and those found worthy will enter Paradise. At issue is, what do the faithful have to do to advance the end-time? Predictably, Judaism, at its end of the continuum, asks the faithful to carry out God’s will as stated from the beginning, sanctifying the Sabbath of creation one time in accord with the Torah. So Judaism looks inward, within Israel, for the salvation of humanity through Israel’s own act of sanctification. Then who is saved at the end, if not all those who acknowledge the one true God? And that will encompass, the prophets say, all of humanity. At the other end of the continuum, Islam holds that no human effort can advance or retard the Last Day. God alone will recall His creation to Himself in His own good time. All human beings can do is prepare themselves for the Day of Resurrection by living daily lives of piety and probity. At the Resurrection all who have died before will be called forth with all who are living to face the accounting of their earthly lives and inherit accordingly either Paradise or the Fire as their eternal abode. And Christianity takes a middle position, insisting that the world as we know it, down to the very bodies we inhabit, is to be changed definitively. But in that transformation, a metamorphosis from flesh to spirit and death to life, the identities that we have crafted during the course of our lives are to endure. All people, with or without an explicit knowledge of the Son of God, have known his image in their human experience: So from the point of view of the eschaton they have fashioned or have refused to fashion an existence which is commensurate with eternity. These topics show us similarity and difference: a series of single continua, different positions within each continuum. The interior logic of monotheism raises for the three religions a common set of questions. But then each religion tells the story in its way, and the respective narratives — in character, components and coherence — shape the distinctive responses spelled out here. That is how the three religions of one God converge and diverge: They converge in their basic structures, which are more symmetrical than asymmetrical, and they diverge in the way their systems work out the implications of monotheism as monotheism is embodied in the continuing narratives, those of Judaism, then Christianity, finally Islam.

Throughout the world, billions of people rely on their faith to lift them above lives of hardship or the banality of arid secularism. For them, belief trumps politics, and efforts to influence them must incorporate faith as part of any appeal. The University of Southern California’s Center on Public Diplomacy organized a March 25th conference on “Faith Diplomacy: Religion and Global Publics” to examine ways that religion should be incorporated into public diplomacy. The conference analyzed how an appreciation of faith can strengthen foreign policy, how particular religions affect the course of international affairs, and how the religious community can infuse the practice of public diplomacy with the intellectual energy born of its beliefs. In his splendid keynote address, Douglas Johnston, founder and president of the International Center for Religion and Diplomacy, noted the reluctance of many governments to address religion and urged those engaged in public diplomacy to “not hide your faith, as normal diplomats do.” Johnston also stressed the importance of going beyond tolerance to respect, rather than “othering” religions that are not our own. One of the foundations of public diplomacy, and this is particularly important in faith-related matters, is listening. Bob Roberts, an Evangelical pastor from Northwood Church in Texas and a conference panelist, told of reaching out to people in Vietnam and Afghanistan and cited the significance of “listening to their stories and finding a common narrative.” In addition to listening, a willingness to undertake difficult missions is part of faith diplomacy. Janice Kamenir Reznik, founding president of Jewish World Watch, described her trip to the Soviet Union during the Cold War and the experience of American Jews reaching out to Soviet Jews, bringing them hope. She called this kind of activism “praying with your feet.” The U.S. government was ably represented at the conference by Victoria Alvarado, director of the State Department’s Office of International Religious Freedom, which recognizes the relationship between religious freedom and national security. But religion remains a secondary factor in U.S. foreign policy. Former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright has suggested that U.S. embassies add religion attaches, but the principle of separation of church and state has, quite unnecessarily, made American officials wary of this. The world is becoming more religious, and to pretend otherwise limits the effectiveness of foreign policy. In the Arab world, for instance, the new order spawned by this year’s revolutions will embrace Islam more fervently than was fashionable among the ousted regimes. If the United States is unprepared to address this heightened significance of religion, it will be relegated to the status of outsider, with diminished influence in the region. Our Center on Public Diplomacy is just beginning its Faith Diplomacy Initiative. Our goal is to help reshape governments’ public diplomacy agendas by stressing the need to make religion an integral part of their approach to international publics.

If they do so, they will embrace reality, and their faith-related public diplomacy efforts are likely to prove much more successful than those of the past.

Is that it? Will no one explain how the poco-poco is considered soul worshipping? Is Zambry afraid of confronting Harussani over this matter?

A dance today, what then tomorrow? The ridiculous ban on yoga a few years ago already damaged Malaysia’s reputation.

Harussani is the same man who forbade us from going to our non-Muslims friends homes for their festival days. So much for Prime minister Najib Abdul Razak’s 1Malaysia interaction.

Harussani is the same man who almost caused a near rebellion when he said that the Manchester United football jerseys should be shunned: “Yes, of course in Islam we don’t allow people to wear this sort of thing. Devils are our enemies. Why would you put their picture on you and wear it? You are only promoting the devil.”

He also said that besides the Red Devils, football shirts of Brazil, Barcelona, Portugal, Norway and Serbia were deemed unacceptable because they had images of the cross or had alcohol brands on them.

As expected, Malaysian supporters of ‘Manchester United’, expressed their anger, on the fan’s websites.

If banning the jerseys is what Harussani and his kill-joy clerics strongly believe in, they might as well ban football.

Football, in Malaysia, has almost a religious following with whole families taking a lively interest in the sport. Even the PM went overboard and declared a holiday when Malaysia won a minor game against Indonesia.

If we can’t dance then what about the DVD’s that promote dancing. They will have to go too. What about the music that accompanies the dance?

Why does the austere Harussani, our politicians and a few lawyers, trip over themselves to see who can make Malaysia the world’s worst joke? Why not just place Muslims in straitjackets?

Malaysia does not need people like Harussani. He is neither the voice of reason nor of moderation.

He causes communities to mistrust each other. He almost caused a lynch mob to assemble at the Silibin church in Ipoh, when he allegedly spread a rumour that Malays were going to be baptized there.

Although many Muslims disagree with Harussani, several liberal Muslims/Malays are too afraid or reluctant to damp out the opposing voices of conservatism. These conservatives play on the Malays’ fears by claiming that by doing certain things, they are doomed in the afterlife.

Harussani does not believe in having information made freely available. He certainly does not like educated Muslims who demand answers based on reason.

Most Muslims believe that religion is not just about punishment, but about education. Unlike Harussani, moderates don’t accept having blind allegiance and acceptance of the faith.

The conservatives like Harussani claim to be defenders of Malays and Islam. They dissuade others from expressing opinions that they don’t want to talk about. They feel slighted at any reference to Malays or Islam. They use the police as a tool and various senior politicians as their minders. These conservatives have managed to silence the non-Malays and any Malay who voices disapproval.

Harussani once described former Perlis mufti Asri Zainul Abidin as a “strange person” who had become “arrogant” after Asri completed his advanced studies in Islam.

Harussani condemned Asri’s need to educate people by saying: “How long do you want to educate a person? The country and this world will be a safer place if we have Islamic laws. When I was in Saudi Arabia I felt very safe.”

Perhaps Harussani could do us all a favour and live in Saudi Arabia. He would be safe, and we would be sane.

No comments:

Post a Comment